|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

About author

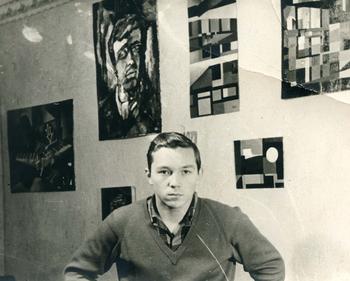

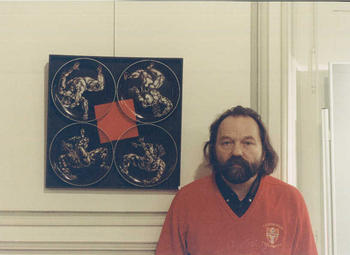

Y.P. is a graphik artist. For a long time he worked with paper material as a drowing and gravure,but during the past 20 years he has been designing on porcelain,creating platters, plates, and especially porcelain eggs. He applies the same techniques as on paper, using different materials. His designs have been influenced by the avant-garde periods of such artists as Malevich, Kandinsky, and Souietine. Some of his designs show the influence of prerevolutionary "Imperial" period. This influence is very apparent in some of his exquisite porcelain eggs. Since 1978 Y.P. has been visiting Western European countries and U.S.A., where he exhibits, sells his works, and teaches his special techniques of porcelain painting. In 1993-2002 he held special classes of porcelain painting in Neuilly-Sur-Seine, France The parallel world of Yury Petrochenkov. Liteyhy prospekt, St Petersburg. A large, cosy apartment in which one can live comfortably. Collections of this and that, antique furniture, a large number of icons, pictures of friends, gifts. In the kitchen - goblets and German beer tankards arranged in a line. This is the home of Yury Petrochenkov, the well-known St.Petersburg porcelain-painter and graphic artist. Yu.P. lives in the very centre of St.Petersburg in a house built in the 19th century in a style which, is whimsically eclectic with towers and bay windows, dragons and spires. From Petrochenkov's living room you can look across to the House of Muruzi, where the celebrated poet Joseph Biodsky lived; round the corner, the gaze is pulled upwards to the domes of the Preobrazhensky Cathedral, but the ringing of the Cathedral's bells, mixing with the dull noise of the street, is only just audible through the firmly closed windows of the apartment. To the left, a little further along Liteyny prospekt, is the freshly painted massive structure of the "Large House", as the headquarters of the former KGB is popularly known. In the 1970s and 1980s Yu.P. was one of the "lefties", as they were then called, in the Association of Experimental Art (TEI). This organisation existed to bring artists together for mutual support and help, to fight the official system of Soviet art, and to put on exhibitions of works by artists belonging to various movements. In the main, these exhibitions were of painting and graphic art: there was very little sculpture. "Objects" had only just appeared on the scene, while "applied art" had from the beginning of the 1960s enjoyed greater freedom and so had no such urgent need of a "non-official" association. At these exhibitions I saw Yu.P.'s works in porcelain for the first time. They stood out for their pronounced, slightly old-fashioned, craftsmanship. Painting was at that time dominated by the expressionist Style with its bright colours and crude, heavy lines. Against this background Petrochenkov's refined, dryish manner was particularly noticeable with, underneath it, the acerbic sense of humour of an artist and critical observer. TEI has long since ceased to exist. Many of its members have left Russia or died; others have become flourishing artists. That epoch has been the subject of numerous historical articles. Modern art criticism, on the other hand, tends either to ignore it or to look down upon its traditions as old-fashioned or frankly commercialised. Yu.P. has not gone abroad, in spite of the fact that his hospitable home has always sheltered many foreigners and he continues to have plenty of friends in the West. He has not, on the other hand, evolved into a "mythological figure" of the age of struggle or exploited his image as a veteran of that age, for all that he must have moments of heroism to recount. Yu.P. does not "go sticking his nose into other people's business" (as he himself puts it), does hot go chasing after fashion, and remains calm in the face of publicity. He is in his middle age, rarely leaves home, and works a great deal. Settledness, thrift, and tradition: these are perhaps the three words that best characterise Petrochenkov's artistic and existential credo. To them we could add: Russian looks, Russian tastes, Russian curiosity (for both his own and other worlds), and assiduity. Yu.P was, and continues to be, a graphic artist, i.e. an artist of intellectual subject-matter and polysemantic imagery (to use Max Klinger's definition). However, he switched to porcelain because he loves things which can be picked up in the hands and which become companions in life. Porcelain is not just line and form, but a way of living; it is rooms, dressers, guests looking at small figures and services. And a way of living implies Tradition. The traditions which Yu.P. follows are various. They include "my home is a cup running over" (as the Russian saying goes) as expressed in porcelain and plenty; the stylish ways of the nobility; but also the bourgeois way of life - with the ludicrous and pitiful characteristics of urban living and its absurdity which is of so much interest to modern art. It seems to me, however, that for Yu.P. the main tradition is the way of life of the intelligentsia, its "interests"and "conversations", its love of collecting - its passion for rare things, for fragments salvaged from the past, and for the graves of our fathers. We all remember the conversations over tea about this and that - about history, politics; anecdotes; current events. Talk that brings forth both laughter and tears. This is where Petrochenkov's subjects and pictures, inscriptions and signs come from. It's as if someone has been sitting as a visitor in your drawing-room, listening to all the gossip, and has then taken a plate, drawn on it a strange pattern, and filled it with surrealistic decorations, Yu.P. says of himself that he lives a recluse's life. To which I would add that he may be a recluse, but he lives in the centre and lives no straightforward life. In both his art and his life - and these two things are almost inextricable - you sense the coming together of Russian positive qualities such as respectability and naivete, cunning and intelligence, quickness. In all respects Yu.P. "is not lightly to be fooled": in his drawings and plates he is a true critic, of all demagogy, stupidity, and slobbishness and cleverly pours irony on all forms of turgidity and self-satisfaction. Yu.P. used to paint large numbers of icons for the Russian Orthodox Church; now, though, he refuses to do so, arguing that the Church is trying to take the place of the Politburo. He has no desire to "surrender himself for all time to come to a particular camp". The way he identifies himself is complicated and problematic. Thus the "New Russians" and the "New Nobility" are not among buyers of his work: for them it is insufficiently beautiful and smells suspiciously of the intelligentsia and all the latter's ideological problems and wounded pride. Western European porcelain, argues Petrochenkov, has always been, and remains to this day, purely decorative, combining extreme technical perfection and refined ornamentation. At the same time, French porcelain, for example, is an essentially utilitarian and prestigious thing. In Russia porcelain, while carrying out the same functions, has always had others as well. Traditionally, it has been a loquacious and demonstrative art form, an educator and teacher - which is hardly surprising given that, as something imported from abroad, it embodied new, non-traditional forms of life and thought. Porcelain was closely bound up with the imperial court and its policies; it sprang not so much from a need for convenience and elegance, as from the ambition to promulgate a certain kind of culture, to compete, or to affirm one's magnificence, splendour, and superiority. Russian porcelain is an art form of national importance; it is full of allegories and lessons, didactic, based on "pictures" and "slogans" which operate as signs. This was the case in the 18th century, in the age of Pushkin, under Alexander III, and even after the Revolution, when the ruling ideology was of a different kind. European decorative and applied art, as is well-known, allotted a special place of honouf to Russian Soviet agitative porcelain, a genre which has no parallels in the porcelain of other cultures. It is a revealing fact that propagandising pottery of this kind was created not by traditional porcelain painters, but by free artists, painters, graphic,artists, sculptors, and experimenters who came to porcelain from outside. For these people porcelain was not a routine, albeit refined, craft but real, living, art which answered the various needs of the moment. Yu.P. also wants to be an artist in the above tradition. He is no decorator, nor does he strive to make things "tasteful". On the contrary, his aim is to attract attention, to amuse and trouble the viewer. He has something he wants to show us and is as surprised by this something as we are. The ornamental motifs employed by Petrocherikov are diverse but mostly familiar to the viewer, reminding him of objects from the surroundings in which he grew up - grandmother's lacework, the frame around an icon, porcelain from the Soviet age, embroidery. But even if the motif is something altogether untraditional, such as brickwork, logs, or an abstract pattern reminiscent of strips of paper or clippings and curls, it nevertheless seems familiar sincfe it bringsto mind objects and images from our native environment, from newspapers and photographs, or from our television screens. Yu.P. is, above all, a graphic artist. He is an inventive master of line and a brilliant calligraphist in a florid style which has something of the museum quality to it while at the same time recalling surrealistic ephemeridae. His manner brings together several unrelated layers and traditions. The first that can't help striking the viewer is his "surrealism" - a style which is modified by strains of 16th -century mannerism. Petrochenkov has "copied" much and produced variations on engravings by the mannerists, on their images of naked bodies twisted into arabesque-like shapes (such as, for example, in the works of Goltsius). Of course, Petrochenkov has also borrowed many of his techniques from Dali, Tangi, and, to a lesser extent, Magritte. Equally, there can be no doubt that on the Leningrad art scene of the 1970s, when Yu.P. was evolving as an artist, all this was seen against the background of the universal passion for Art Nouveau, Beardsley, alid the St.Petersburg turn-of-the-century group "Mir iskusstva" (from Bakst to Narbut, Miliotti, and Chekhonin). In Petrochenkov the dryness of the surrealist style of drawing and an emphasis on the steely virtuosity of the mannerists gain the upper hand over the sentimentality and elegance of Mir iskusstva. Just as strong a role as that of the 16th century in Yu.P.'s styl is played by the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th - by classicism, Empire, bidermeyer, and by their successors. Yu.P. takes from the latter styles not elegance, bouquets, grids, deep cobalt, or delicate shades of grey, lilac, and lemon-yellow alone so much as the motifs of severely ornamental order, a repetitiveness of elements, symmetrical compositions, and, of course, a tendency for richly detailed narration. There is, however, one more highly important ingredient in Petrochenkov's style which has to be mentioned if that style is to be correctly described. This is a certain quality of mechanicality and reproducibility which derives, in my opinion, from the influence of the newspaper, the magazine-type illustration, and the caricature. The latter, I should make clear, is not said in reproach. It is exactly such moments of dryish conventionality that distinguish Yu.P.'s decorated porcelain from the "living" tradition of porcelain-painting with its emphasis on improvisation and freshness of brushwork and bring it closer to conceptual art, i.e. to art whose object is not the organic aesthetics of a felt material (porcelain, brushwork, gold, colour), but ironic play with styles, techniques, and with the significance of techniques in culture. This explains why Petrochenkov enjoys no recognition among painters who belong to the "true" tradition of porcelain decoration. In his work Yu.P. reveals, and strives to continue to develop, another facet of porcelain - not its sensory character and the unity of material, form, and painted decoration, but. its semantic significance, technical qualities, its popularity, and even its status as an "item of mass consumption". Porcelain entices the buyer: it is simultaneously an item of luxury; a masterpiece; and an expensive and practically useless thing whose main value is as a sign. But at the same time it is always something mass-produced, not absolutely unique, reproducible. In this duplicity lies much of porcelain's charm. Easter eggs. Plates to be hung on walls. China services. Clocks. All the genres practised by Yu.P. are traditional, yet he interprets each of them in a way that brings out in it an unconstrained diversity of meanings. His eggs have long since lost their direct connection with religion; nor are they simply of impressive grandeur. His plates are not so much pieces with to embellish a wall or dresser with a decorative spot of bright colour as enigmas and patterns which tickle the imagination. His clocks, in the shape of eggs or his own head are absurd, "inconvenient" objects. The traditional quality of the genres used by Yu.P. is fictive, a matter of external conventions, while the artistic problems which exercise him have no direct relation to the forms associated with these genres. He is not interested in decorating planes and surfaces; what attracts him is deep space, illusory depth, volume, apertures, connecting and multi-layered structures. His "Easter" eggs are domes, hollow spheres, little houses, heads, hipped roofs, etc., etc. His plates likewise mostly demonstrate dynamic motifs - spinning, falling, soaring; shapes here intertwine to form knots or curl or multiply in swarms. All this requires subtle techniques of perspective, foreshortening, and chiaroscuro. Here too Yu.P. shows himself to be a great conjurer, a true illusionist. Petrochenkov's imagination serves up not just optical tricks (in the spirit of Esher and others), but also non-real, possible situations such as cause the heart of the porcelain-lover to stall. "And there goes our favourite plate" (an inscription by Yu.P.) is a constant theme of Petrochenkov's gloomy joking. Two plates joined together to form a single plate with broken-off edges; a rounded form which develops corners as the viewer looks on; tears which disfigure the body of the porcelain: all these absurdist effects are encountered frequently in other art forms, but not in porcelain, which was neglected by the avant-gardists and soon abandoned by the expressionists (Suetin's experiments failed to establish any long-standing tradition). In the traditional understanding, porcelain is an inert sphere which resists outside influence. It should be noted; however, that in their approach to porcelain the avant-gardists chose to concentrate on form and colour, Yu.P., following the Russian tradition of entertaining didactics, brings out in porcelain an altogether different quality, one which has been explored since the Baroque age - its ability to take on different meanings and images, its openness to different types of illustration - and all this in the form of a theatre of figures and signs. It should be noted that Yu.P. almost never invents new shapes, but buys porcelain forms ready-made from the factory. A specialist in the semantics of porcelain, he gets these taciturn utilitarian shapes to talk, realising and fixating their tales in history (his porcelain, bitingly relevant in everyday life and in the political context, immediately becomes part of a collection, joins a museum of pictures and locutions). In this way fbf Petrochenkov porcelain is a means of creating a small cultural kunstkamera (cabinet of curiosities) in which tradition, relevance, uniqueness, fleeting significance and the culture of mass consumption come together to form an integral whole, as in life itself. Talking of himself, Yu.P. uses words from the famous film , "I'm not in the Soviet camp and I'm not a cadet" - and goes on, more seriously, "I'm not a modernist, I'm not an avant-gardist, I'm the last representative of... ". But last representative of what? It was in order to formulate a reply to this by no means simple question that Yu.Ph.asked me to come and see him and started talking about his work, his travels, his studio, all the time emphasising his principle of non-interference, of restraint from importunity: "No one knows me, I don't go sticking my nose into other people's business; I'm known in those places and by those people where and by whom I need to be kriown, and that's all". No natural light enters Yu.P.'s studio. It is full to bursting with all kinds of instruments and gadgets. The kiln gives off a fierce heat. This, he says, is "my alchemy. Here I work non-stop, like a labourer". He is, of course, a "labourer" of a special kind - gifted, knowledgeable, endowed with imagination and exacting taste, like the "aristocrats" whom he regards as his potential buyers. In my opinion, Yu.P. is indeed representative, albeit not the last representative, of that classical Russian figure - the skilled craftsman and "observer out of the comer of the eye". From his basement he watches keenly what is going on out there, in the world Outside, tuning in to what people are talking about, what makes people laugh - and then transfers all this to his own sphere, fusing that which has merely ephemeral relevance with the noble substance which is porcelain. This labour and this objective material, with which he straggles day and night, gives him a sense of balance in life. It endows him with freedom and the right to make fun of people and life. The world of Yury Petrochenkov is indeed a parallel world. However, like every parallel, it is the result of a sideways movement, a doubling or reflection of an original line. Thus it in fact has a direct relation to that world - the world of politics, passions, and "contemporary art" - with which Yu.P. would seem to have nothing in common, and so forms part of the "cobalt grid" of contemporary Russian culture. One of Yu.P.'s pieces of porcelain bears a very telling inscription: "Freedom! Give us freedom in such a way that there will always be not quite enough of it, so that we can always continue to ask for more". A thought which is highly typical, very Russian, and very local in character. Its artistic implication can be expressed as follows: let us join tradition and reject permanent revolution, but in such a way as to cunningly keep an eye on it from the cosy teremok (traditional Russian tower-chamber) of the parallel world. I.D. Chechot back |

|

|